By now you have read Blake Snyder’s two books, Save the Cat and Save the Cat Goes to the Movies and know the 15 story beats of successful Hollywood screenplays and the 10 generic film patterns Snyder calls “genres.”

If you missed Part 1 and 2, you can find them through the links below.

In this lesson, we use Blake’s story beats to flesh out our basic story structure, but first, let’s do a quick review of Part 2.

In Part 2, you learned a successful novel is structured and emotionally engaging. And that it’s built, one scene at a time, on a three act skeletal frame.

You learned that the first rule of a successful story is to entertain, that it proves an enduring psychological truth and that it is emotionally engaging.

As a minimum, a story will contain a main character who is driven to achieve an objective but faces conflict as someone, or something, attempts to stop him.

Finally, a story concludes with an emotionally satisfying ending where the main character has changed or failed to change.

You learned some creative personalities have a dark side that might manifest as anxiety and depression.

To protect against this, and to make your novel writing journey healthy and pleasant, I hope you now have the aid of a friendly critic or two, some cheerleaders, and at least one person you can trust.

These people will help you keep a balanced perspective as you dive deeply into the writing process.

You learned that writing a novel is much like putting a puzzle together after you have dreamed into existence the pieces. This is why you write down your story ideas as they come to you.

In order to keep the creative channel open, you know to relax as much as possible and you’ve begun collecting people’s names to use for your characters.

Basic Story Structure Review

After reviewing basic story structure and making a tiny adjustment, I’ll overlay Blake Snyder’s 15 story beats onto the three acts. This will create a structural foundation for nearly any story imaginable.

First, let’s review the basic three acts.

Remember, a satisfying story creates an emotional response in the reader. It all begins with structure. To paraphrase Snyder, story is structure, a precisely made mechanism of emotion.

Life is structured in three acts. We are born. We live. We die.

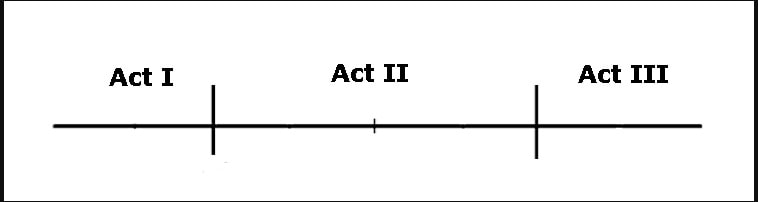

Likewise, a story has three acts: Act I, Act II and Act III.

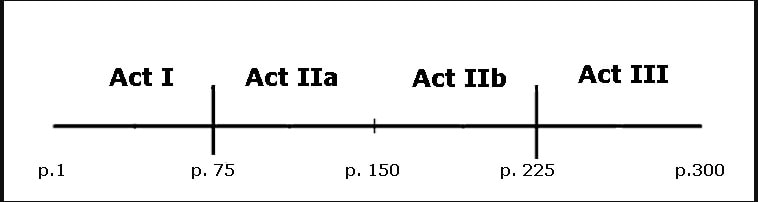

If we divide Act II in half, we’ll have four equal parts. So, if we plan to write a 300 page novel, each part will be 75 pages long.

Now we have the most basic skeleton for writing a novel. As we plan and write, instead of trying to hold an entire 300 page novel in our head, we can focus on just 75 pages at a time.

A novel typically has several storylines. For example, the primary goal of the main character might be to save the world from nuclear holocaust, but he also wants to win the heart of the beautiful Swedish diplomat.

In this example, saving the world is the A story and getting the girl is the B story. The B story and any additional story line is not introduced until Act II.

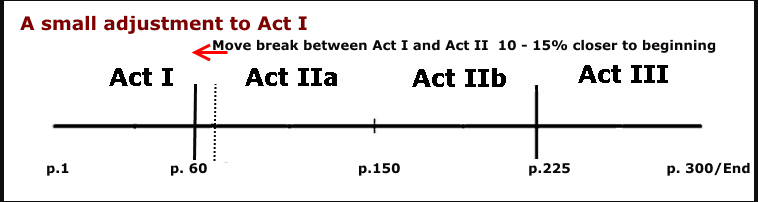

A Small Adjustment to Act I.

Here’s a little trick to get the reader into the story faster. Move the break between Act I and Act II closer to the beginning of the story by about 15%.

In the case of our hypothetical 300 page novel, that means moving the break from page 75 to page 60. This adds about 15 pages to Act IIa.

With this adjustment in mind, we’ll now review Blake Snyder’s 15 story beats and then use them to build a more detailed generic story structure.

Snyder’s Story Beats Adapted for the Novel.

In reading Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat and Save the Cat Goes to the Movies, you learned his 15 story beats and his 10 movie genres, and you saw how these were successfully employed in popular movies.

Mr. Snyder’s use of the word “genre” to describe movie types might be confusing when we try and carry it over to the world of novels. Snyder’s movie “genres” do not relate to novel genres. That’s a different kettle of fish.

Snyder’s movie “genres” are a great place to begin imagining your story, but if you wish to write in a specific novel genre you will need to study successful novels in that genre.

I’ll cover this in more detail in Module V where I show you how to tease out the formula of any novel. However, your ability to do this is dependent on your understanding of story structure, so let’s first get that down.

To fully understand the following story beats, refer to Save the Cat.

Mr. Snyder’s clever interpretation of story beats is uniquely his and justly copyrighted. I’m grateful for the playful vocabulary he has introduced to the process of story creation. Let us play.

In the following chapter, I expand on each story beat as it relates to a novel.

Approximate page numbers are included for a hypothetical 300 page manuscript, but page numbers shift during rewrites, so let the pace and integrity of your story dictate where the story beat ultimately ends up.

As we walk through the story beats, allow each beat to focus your imagination and stimulate ideas for your story.

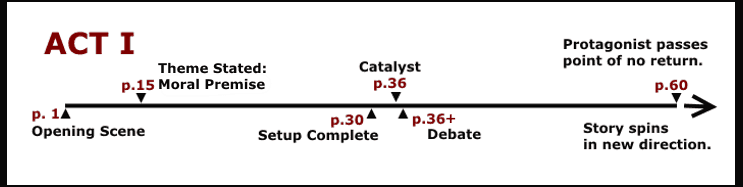

Act I

The Opening Scene (p.1-3):

A lot must be accomplished in this scene. It hooks the reader, establishes the tone of the story, introduces the main character, establishes point of view and shows the main character in her natural element.

At the end of your novel, the final scene will be contrasted with the opening scene to show how much the main character has changed or failed to change.

Don’t try to write the perfect opening scene before writing the rest of your novel. Until you know everything about your story, you won’t have the insight to write the best beginning.

Many novelists write the opening scene last.

I usually cobble together an opening scene when I write the first draft and then continually improve on it as I write the rest of the story and subsequent drafts.

I like to begin a novel in the middle of a scene. This catches the reader off-guard and entices her to read further. Typically, I’ll also open a novel with a question in dialogue.

Here’s how I began Some Glad Morning: “He’s dead, ain’t he?“

Theme Stated (p.15):

Somewhere around page 15 of a 300 page manuscript there is a clue to what the story is really about. A snippet of dialogue from someone other than the lead delivers this clue.

Your story is a dramatic argument which proves some principle of life is true, such as money doesn’t buy happiness or love is eternal or good revails over evil.

The statement of the theme is indirect and will not be consciously noticed by most readers.

Here’s how I stated the theme in my novel Some Glad Morning.

Ransom, the main character, is the son of a sharecropper, he’s about to leave for World War I and gives his mother some wild flowers he picked beside the road.

He apologizes that the flowers aren’t as pretty as the flowers in the landlord’s garden. His mother replies:

“The prettiest flower ain’t always the sweetest.”

Some Glad Morning then proceeds to prove this is true.

Although, I doubt most readers are consciously aware of the theme, the logic resonates with their subconscious to create a satisfying reading experience.

Later you’ll see that the theme is actually half of the moral premise. I’ll introduce you to the moral premise at the end of this module and we’ll explore it in more detail in Lesson III.

Set-up (p.1-30):

By about page 30, the set-up for your story is complete.

All of the primary characters have been introduced, either directly or indirectly. Direct introductions are preferred because they are more memorable.

This is also where you reveal the main character’s weakness or flaw, that one thing he must remedy before he can defeat the bad guys and reach the story’s objective.

Finally, the set-up establishes the main character in his natural environment before the Catalyst rocks his world and forces him into action.

Catalyst (p.36):

The catalyst creates a moral dilemma within the main character and sets the story in motion.

The catalyst might be the main character being served divorce papers or getting fired or framed for murder or the death of the love of his life.

It could be a zombie apocalypse, winning the lottery or losing everything. It could be anything.

In Some Glad Morning it’s when Ransom’s reads the letters from his commander’s fiance.

At the moment of the Catalyst, life as the main character knows it is forever changed.

Debate (p.36-60):

It’s human nature to resist change. That’s why the main character must struggle with what the catalyst has caused.

The first response to change is usually to fixate on the past and how the world was before the great cataclysm.

Between the catalyst and the break into Act II, the main character resists the changes forced upon him.

Break into Act II(a):

After resisting the change caused by the catalyst, the main character, knowing the hazards and uncertainty he will face, chooses to take action and departs the old world.

It is essential that this is the main character’s choice.

Passing into Act II, it is as if the main character has stepped through a door that locks behind him. There is no going back. Nothing will ever be the same again.

There must be a clear and dramatic point of departure as the main character passes into Act II. The reader must have no doubt that something important has just occurred.

Furthermore, the reader must have no idea of what happens next as the story spins in a new direction.

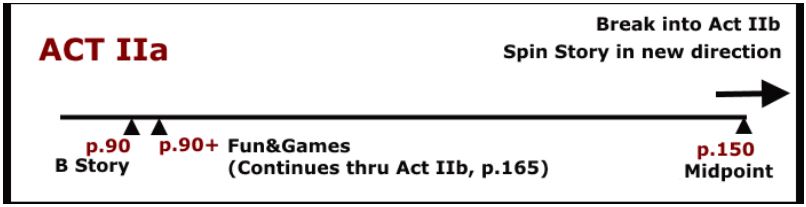

Act IIa

B Story:

In Act IIa, we introduce other story lines, such as the love story if there is one. This is also where all the main character’s relationships are examined as they relate to the story’s theme.

The theme itself is overtly explored here as well.

Fun & Games:

This is the heart and soul of your story. This is where you deliver the goods. If you promised the reader a story about a transgender ax murderer, this is where they get it.

Midpoint (Break into Act IIb-p.150):

Here the stakes are raised. Not only can the main character die if he fails to reach his objective, but now the love of his life might die with him.

On page 84 of Save the Cat, Snyder discusses how the midpoint scene is matched with the “All is Lost Scene” which comes later. Understanding this match-up is essential to balancing your story.

The main character passes into Act IIb as if he steps through a door that locks behind him. There is no turning back. Again, the story spins in a new direction.

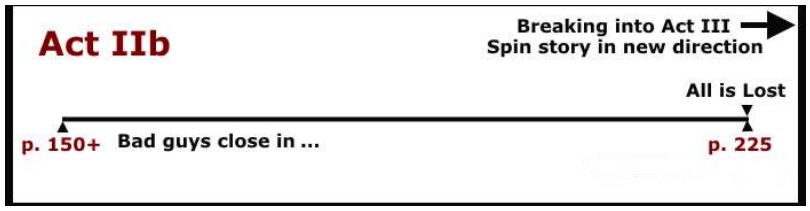

Act IIb

Bad Guys Close In (p.150-225):

There’s more to this than meets the eye. Mr. Snyder’s casual use of “Bad Guys” means that force opposing the main character, otherwise known as the antagonist.

The antagonist might actually be bad guys like in the movie Home Alone.

Or, it might be nature, like in the movie The Perfect Storm.

Or something within the lead character’s personality such as greed, selfishness or an obsession.

Or anything he must defeat before he can reach the story’s objective.

All Is Lost (p.225):

This beat is a mirror image of the mid-point scene.

Here it appears the main character is completely defeated and the reader cannot imagine how the main character can possibly win.

Break into Act III (p.225):

The main character passes into the Act III, stepping through yet another door which locks behind him, spinning the story in a new direction.

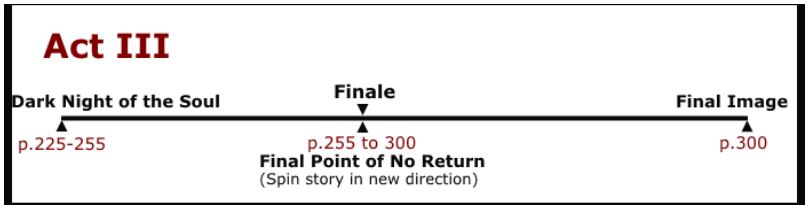

Act III

Dark Night of the Soul (p.225-255):

In this beat, we go inside the main character’s head to experience “the All is Lost” and “Whiff of Death” as he is experiencing it.

This beat does not have to be long, but there is an advantage if it is. You want the reader to fully experience the main character’s despair.

This is a critical story beat and I want the reader to linger on the edge of the abyss.

By taking the reader to the brink of darkness, she is primed to have a deeply satisfying cathartic experience at the end of the novel.

I tend to overwrite this beat and then depend on my beta readers and editor to tell me if I need to dial it back.

Here’s a snippet from the Dark Night of the Soul beat in Some Glad Morning. My main character, Ransom, is lying in the bottom of a small wooden boat at night, drifting on an outgoing tide.

“Lord,” Ransom said to the stars, “why was I made to be so miserable? Give me to the ocean. Feed me to a whale. Strike me dead with a bolt of lightning.”

He lay still, letting the tide take him as he tied his brain into ever tighter knots, each knot cinched with shame and self-loathing.

Some Glad Morning

Finale (p.255-300):

Here the A and B story lines intersect to reveal the secret for defeating the bad guys.

The main character realizes if he’d stop being so damn selfish he could save his marriage or he’d get over his fear of technology he could use the photon transmogrifier to shrink the nuclear bomb into a firecracker and save the world.

This is the final point of no return. The main character is committed to action. There’s no going back.

Final Image (p.300):

The final image contrasts with the opening image to demonstrate

unquestionable evidence that the world has indeed changed.

This is often the most memorable image of a novel. It must resonate emotionally with the reader to be effective and satisfying.

Before I begin writing a novel, I plan it out and have at least a rough idea of how my story will end.

Once I know the ending, I can fashion every scene to serve the end, so the reader is delivered, scene by scene, to an ending that is surprising, yet believable, and emotionally satisfying.

The Essential Moral Premise.

…psychological moral dilemmas are at the heart of every successful story.”

Stanly D. Williams, Ph.D., The Moral Premise, p.17

Earlier, I wrote that your novel is an argument that proves your story’s theme. That is only half true, because the theme of your story is only half of a larger concept.

To achieve the deepest emotional experience for the reader, your novel must prove an enduring psychological truth.

Other authors might describe this psychological truth as the premise, or spiritual spine, or controlling idea, or hidden truth, or universal truth, or emotional through-line or informing vision or the moral premise.

Regardless of what you call it, it is the dramatic heart of your novel. It is the single spark that ignites your entire story.

To avoid confusion, I’ll call this enduring psychological truth the moral premise.

This is what Dr. Williams calls it in his comprehensive book The Moral Premise which is a must read for anyone who is serious about writing a successful novel.

The Moral Premise is a natural part of all successful narrative stories. The Moral Premise was written about by the ancients and it is still a foundational necessity of all stories today, whether those stories are carried on by oral tradition, in print, on the stage, on television, through the Internet… or through whatever else comes along…

[The Moral Premise has] been around for thousands of years, since stories were first told, and …it’s proven to be one of the most fundamental structural aspects of storytelling.

Williams, The Morale Premise, Preface.

The reader may not consciously recognize the moral premise.

However, when properly rendered, it will emotionally resonate with her and profoundly deepen her fulfillment for reading your novel.

Lajos Egri points out in his book, The Art of Dramatic Writing, that the premise for Romeo and Juliet is “Great love defies even death.”

In MacBeth, Egri states the premise is “Ruthless ambition leads to its own destruction.“

Michael Hauge, author of Writing Sceenplays that Sell, writes that the premise of the movie Tootsie is: “For relationships to succeed, they must be based on honesty and friendship.”

Your novel is an indirect, almost subliminal, argument that proves the moral premise of your story.

Using the life and circumstances of your main character, and those around her, your job is to reveal, scene-by-scene, why your moral premise is true.

A moral premise also makes the job of writing much easier. It’s like a compass that directs the development of every character and every scene.

You don’t have a story until you know why your main character does what he does.

It is your main character’s inner motivation that reveals who he really is and governs his outward action as he strives to reach the story’s objective.

Now, here’s where it gets interesting, the challenges the main character must overcome are all rooted in a single psychological, spiritual or emotional issue within the main character.

In the course of a story, the main character will meet all sorts of physical obstacles as he tries to reach some physical goal.

However, these physical obstacles actually represent a single spiritual, emotional or psychological obstacle inside the main character’s psyche.

Before the main character can get past the physical obstacles, he must first come to terms with the internal psychological obstacle that is defeating him.

In other words, a story is the outward physical manifestation of the main character’s internal struggle of conflicting values. This is the seed of your story.

Your novel grows out of the psychological moral dilemma within the main character.

During the story, the main character will be offered a solution to his psychological situation. The offering of a solution is known as an offering of grace.

If he accepts the offering of grace, the conflicting values within him are resolved and the story ends happily. If, however, he rejects the solution, the continuing internal conflict drives the story to a tragic end.

The main character’s internal struggle is what the story is really about.

While the physical and explicit story or plot line is what a movie is about, the psychological and implicit story or plot is what the movie is really about.

For instance, on the physical, explicit level Die Hard is about a New York cop who alone battles an office tower full of desperate, selfish thieves.

But on the psychological or Moral Premise level the movie is really about the depth of one man’s selfless love for his wife.

Williams, The Moral Premise, p.XXII

The moral premise is so powerful and so essential to the success of your story, it would take a book to fully explain it.

Fortunately, Dr. Stanley D. Williams, PhD has written just such a book, appropriately called The Moral Premise. I highly recommend you read it.

Writing a novel is like telling a big fat lie. The most believable lie has a kernel of truth. In a novel, that kernel of truth is the moral premise.

For now, remember that a story begins with a moral premise, so as you dream your story, look for it.

Also, look for the main character’s moral dilemma in the movies you watch and the books you read.

Notice how this internal conflict drives the actions of the main character and shapes every aspect of the story.

What’s Next?

By now you might be thinking this is a lot to think about. It certainly is and there’s more to come.

However, fear not, I have a system that makes it all quite manageable. I’ll tell you all about it when the time is right.

For now, just get familiar with the logic of how a story fits together. When you watch a movie or read a novel, look for the story beats and the main character’s moral dilemma.

In the next lesson we explore the moral premise in depth. To get the most out of it, please read Dr. Stanley D. Williams excellent book The Moral Premise.

The moral premise is the secret of secrets of story creation. Once you understand it, you’ll have a deeper understanding of novel writing than most novelists.

Plus, the moral premise brings the entire novel planning process into sharp focus. It makes writing faster and easier, and produces an infinitely more enjoyable novel.

Read The Moral Premise, continue to dream the pieces of your novel, make notes and collect interesting names you find along the way.

In Part 4 of the How to Write Your First Novel series, we take a deep dive into the moral premise and discover how it shapes every word of your novel.