I hope by now you’ve had time to read Blake Snyder’s two books, Save the Cat and Save the Cat Goes to the Movies. I hope you’ve also read The Moral Premise by Dr. Stanley D. Williams.

The books I recommend in this course are essential to fully understanding this method of imagining, planning, and ultimately writing a successful novel. Not only do I highly recommend that you read these books, but I recommend you read them again as you plan each of your novels.

There are several books I read as I plan a novel. Save the Cat, Save the Cat Goes to the Movies and The Moral Premise are three of them.

I’ve read these books many times and I’ll read them again as I plan every novel I write. By reading them as I plan a novel, I’m reminded of things I would otherwise neglect to consider.

I encourage you to do the same. This habit will accelerate your mastery of writing novels and boost the quality of your writing to new heights.

If You Haven’t Completed Parts I, II, and III.

If you haven’t completed Parts 1, II, and III of this series, you can click the corresponding link below to and go to that lesson.

- How to Write Your First Novel, Part I.

- How to Write Your First Novel, Part II.

- How to Write Your First Novel, Part III.

Here’s a brief review of what we’ve covered so far:

In lessons I, II and III, you learned a generic story structure you can use for most any novel you’re writing.

I also introduced you to the Moral Premise and how it determines the motivation of your main character and the handful of supporting characters closest to your lead.

The Moral Premise also guides each scene.

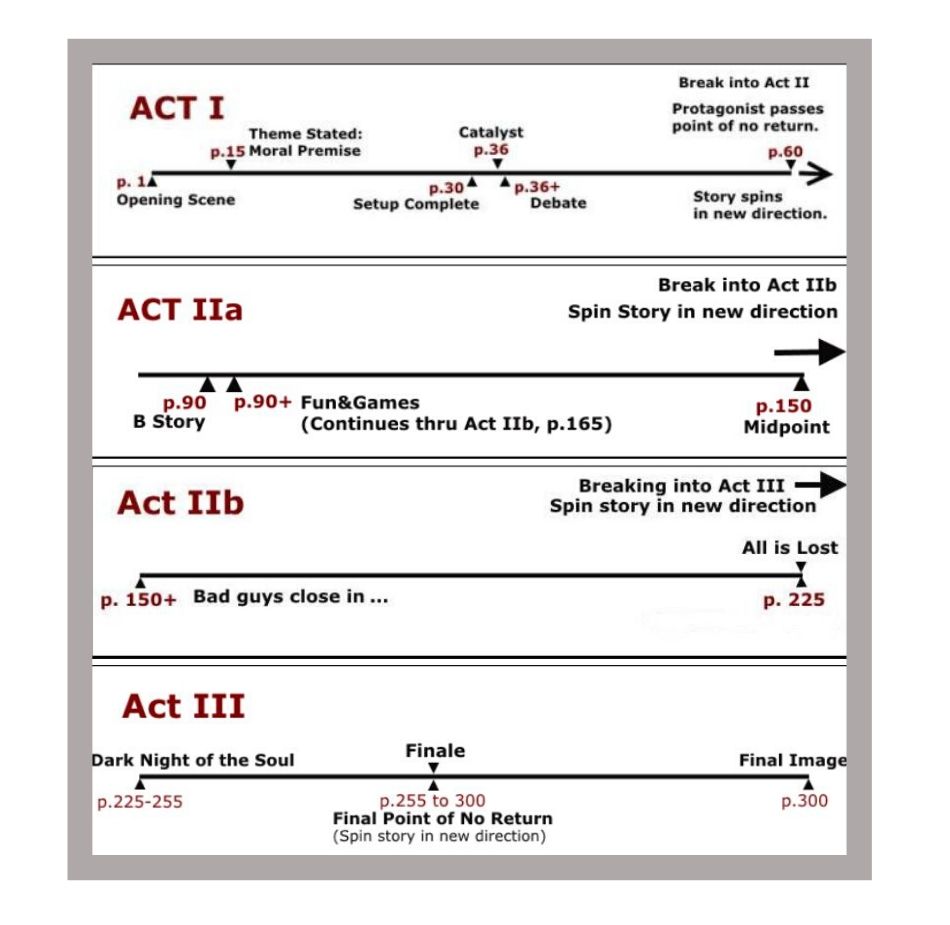

I’ll discuss the Moral Premise in more detail in a moment. For now, look over the graphics of our generic story structure. The details of this generic story structure are discussed in lessons I, II and III and in Blake Snyder’s two books, Save the Cat and Save the Cat Goes to the Movies.

On a timeline, the generic story structure looks like this:

The Moral Premise.

…psychological moral dilemmas are at the heart of every successful story.

Stanly D. Williams, Ph.D., The Moral Premise, p. 17

A story must have focus. Otherwise, it will just meander all over the place and confuse the reader. You don’t want that. A confused reader isn’t a reader for very long.

The Moral Premise gives your novel focus. It shapes the behavior of the primary characters and dictates how each scene is constructed.

When you want to know if a novelist is serious about their craft, ask them about the Moral Premise of their current project.

If they don’t know what you’re talking about, they really need to know about this course.

It’s all about the internal struggle.

In lesson III, we learned that a story is the outward, physical manifestation of the lead character’s internal struggle with a moral dilemma, otherwise known as a conflict of values.

Yes, there might be sexual liaisons with transgender midgets, romance, infinite magic, sword fights, wizards, space wars, death stars, even nuclear Armageddon in your novel.

However, all of that is merely external evidence of the struggle raging within your main character.

It’s not easy being human.

It’s not easy being human. Ultimately, for a novel to be satisfying it must give the reader guidance for how to do this thing called life, because deep within our soul, this is what we all seek.

Here’s what Vogler has to say about it in the foreword to The Moral Premise:

I jump up and down in my classes and in Hollywood story

Christopher Vogler, author of The Writer’s Journey.

meetings about the desperate desire of the audience for

entertainment that embodies some moral principles, some

guidelines for ethical living, some prescription for a healthier

world and a saner life.

Guidance about the human condition can be thought of as enduring psychological truth.

There are many of these truths, jewels of wisdom that have evolved through countless generations and been passed down to us in the form of myth, fairy tales, philosophy, spiritual teaching and the deepest foundations of religion.

The Dramatic Heart of Your Story:

The Moral Premise is the dramatic heart of your novel.

The Moral Premise is a natural part of all successful narrative stories. The Moral Premise was written about by the ancients and it is still a foundational necessity of all stories today, whether those stories are carried on by oral tradition, in print, on the stage, on television, through the Internet… or through whatever else comes along…

[The Moral Premise has] been around for thousands of years, since stories were first told, and …it’s proven to be one of the most fundamental structural aspects of storytelling.

Williams, The Morale Premise, Preface.

The reader may not consciously recognize the Moral Premise.

However, when properly rendered, the Moral Premise will emotionally resonate with the reader and profoundly deepen her satisfaction with your novel.

Your novel is an indirect, almost subliminal, argument that proves the Moral Premise of your story.

Using the life and circumstances of your main character, and those around her, your job is to reveal, scene-by-scene, why your Moral Premise is true.

A Moral Premise also makes the job of writing much easier. It’s like

a compass that directs the development of the main character, those closest to him and every scene.

You don’t have a story until you know why your main character does what she does.

In the early stages of imagining a novel, search for the Moral Premise. You cannot begin to focus your story or shape any of its

elements until you know the Moral Premise.

A Closer Look at the Moral Premise

To fully understand how the Moral Premise builds on our generic story pattern and how to embed it in your novel, you really must read Dr. Stanley D. Williams’ book The Moral Premise.

In the second half of The Moral Premise, Dr. Williams takes you step-by-step through creating a solid Moral Premise and weaving it flawlessly throughout your novel.

Later, we build on Dr. Williams’ teaching when we begin to solidify the planning of your novel with the help of a storyboard.

Your story grows out of a conflict of values within the main character.

It is your main character’s inner motivation that reveals who he really is and governs his outward action as he strives to reach the story’s objective.

In the course of a story, the main character will meet all sorts of physical obstacles as he tries to reach some physical goal.

However, these physical obstacles actually represent a single spiritual, emotional or psychological obstacle inside the main character’s psyche.

Before the main character can get past the physical obstacles, he must first come to terms with the internal psychological obstacle that is defeating him.

In other words, a story is the outward physical manifestation of the main character’s internal struggle of conflicting values. This is the seed of your story.

Here’s a very important point…the supporting characters who are closest to your main character are also struggling with the same Moral Premise.

In the supporting characters closest to the main character, we see wise or unwise attempts to solve the same issue the main character is dealing with.

The Moral Premise Must Be True to Reality.

Your readers will only relate to the Moral Premise of your story if it is true to reality.

Story Theme and the Moral Premise.

The Moral Premise is first introduced to the reader when the theme is stated early in Act I.

The theme is actually half of the Moral Premise Motivation Statement as defined by Dr. Stanley Williams in his book The Moral Premise.

Here’s the generic Moral Premise Motivation Statement as presented in the book, The Moral Premise.

[psychological vice] leads to [physical detriment] but

[psychological virtue] leads to [physical betterment].

Here’s how the Moral Premise Motivation Statement for the movie

ANY DAY might look.

Believing in only yourself leads to pride and ruin, but believing in something bigger leads to hope and salvation.

In a moment, I’ll look more closely at the movie ANY DAY, but for the now let’s move on to a critical element of the Moral Premise, the Moment of Grace.

Moment of Grace

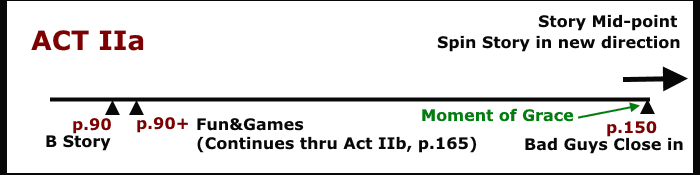

Halfway through the story, at the end of Act IIa, just before the main character passes into Act IIb, he is offered a solution to his psychological situation.

This moment, according to Dr. Stanley Williams, is the Moment of Grace.

If the main character rejects or ignores the solution to his psychological situation, he will remain unchanged at the end of the story and the story will end tragically.

However, if the main character accepts the solution, he will change over the course of the second half of the story and the story will end happily.

Moment of Grace occurs at end of Act IIa:

In a hypothetical 300-page novel, the Moment of Grace will appear near page 150.

The Movie ANY DAY.

In the books Save the Cat, Save the Cat Goes to the Movies and The Moral Premise, movies are used to demonstrated story beats, theme, the Moral Premise and the Moment of Grace.

In some films it can be difficult see these story elements. Recently, I stumbled onto a movie that so overtly uses these story elements it’s easy to see how they are employed.

The movie is ANY DAY, written and directed by Rustam Branaman and staring British actor Sean Bean. It’s streaming on Netflix.

Admittedly, the film is flawed and morally heavy-handed. It’s been rightfully panned by critics as being a morality play. No writer wants to be accused of writing a morality play.

Keep that in mind. The reader, or audience, should not be consciously aware of the Moral Premise.

If they see it coming, the story will appear as if a pompous, greater-than-thou author is preaching to the unwashed.

No one likes to be preached to.

ANY DAY: Theme, Moral Premise and Moment of Grace.

ANY DAY is the story of a violent man with an addiction to alcohol. In the opening scene, the main character Vian, kills a man with his bare hands.

The Catalyst is his release from prison 12 years later.

At about 17 minutes into the movie we are shown the story’s theme written in a simple declarative sentence. Vian, his sister Bethley, and her son Jimmy are walking out of a grocery store.

Behind them, a Lotto sign says: “Believe in Something Bigger.”

The movie’s theme is very similar to step 2 of the 12 Step Program for overcoming addiction that states; “We came to be aware that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.”

The theme is only part of the Moral Premise. The full Moral Premise cannot be understood until the Moment of Grace at the middle of the movie.

At about 40 minutes into the movie, as we approach the midpoint, Jimmy offers Vian a copy of Ernest Hemingway’s novel, The Old Man and the Sea. This is the story’s Moment of Grace.

The Moment of Grace.

If you haven’t read The Old Man and the Sea, this gesture may seem obscure, so let me give you a quick review.

The story takes place in Cuba in the early 1950s. A poor and elderly fisherman has gone 84 days without catching a fish.

Determined to break his spell of bad luck, he takes his small open boat far beyond the waters he and the other fishermen usually fish.

All alone on the ocean and out of sight of Cuba, the old man hooks a great fish on a hand line. Later we learn the fish is an 18 foot-long swordfish weighing about 1500 pounds.

The old man struggles to land the fish for nearly three days.

Finally, he manages to land and kill the massive fish. It’s much larger than his boat and the old man must tie it to the side with the carcass mostly in the water.

The old man is so far from his village that sharks eat all the flesh off the bones of the great swordfish before he can get home.

The old man is nearly dead himself when he arrives, with nothing to show for his struggle. He says to the bones, “Fish that you were. I am sorry that I went too far out. I ruined us both.”

In that line of dialogue, we see pride has caused the old man to kill for nothing.

The same is true of Vian in the movie ANY DAY.

The Moral Premise for ANY DAY could be stated like this:

Believing in only yourself leads to pride and ruin, but

Believing in something bigger leads to hope and salvation.

Other characters in ANY DAY struggle with the same issue.

Bethley, Vian’s sister, finds comfort in the church.

His boss, Roland, played by Tom Arnold, is a recovering addict who attends 12-Step meetings and believes in a higher power.

Jimmy, Vian’s nephew, ultimately reveals there that there is indeed something bigger to believe in.

This is how other characters explore various sides of the same issue to prove the story’s theme.

More Movies: STAR WARS & MR. BROOKS

STAR WARS

Another movie that could share the same Moral Premise as ANY DAY, but isn’t as obvious, is the original STAR WARS: EPISODE IV.

In STAR WARS, The Force is the bigger thing to believe in. Note the Moment of Grace and how the theme is stated.

STAR WARS conforms to a story pattern slightly different than our generic story pattern.

It follows the mythical story pattern of the hero’s journey, which I cover in more detail near the end of this lesson.

MR. BROOKS

One of the tightest movies I’ve seen in years is MR. BROOKS, staring Kevin Costner, directed by Bruce A. Evans and written by Bruce A. Evans and Raynold Gideon.

Here, the theme is addiction…addiction to killing people.

In the movie, Mr. Brooks, played by Kevin Costner, states the theme at a 12 Step meeting held inside the sanctuary of a church.

Mr. Brooks says, “Hi. My name is Earl. I’m an addict.”

In MR. BROOKS it’s more challenging to identity the theme, the Moral Premise and story beats because the script is so well written.

This is the kind of subtlety you should shoot for in your own writing.

Notice in the opening scene how Costner blows his wife a sweet kiss, endearing him to us.

Later we discover he is a monster of the highest magnitude, yet we remain bonded to him throughout the movie.

This is the power a simple act of kindness has to bond the reader or audience to the main character.

Also, notice how every scene relates to the story’s Moral Premise.

This is a very important detail. In your novel, every scene must relate to the Moral Premise of your story. Otherwise your novel will lose focus.

MR. BROOKS is a good example of what happens when the main character does not accept the offering of grace and does not change.

Finally, pay attention to how Costner, his alter-ego Walter, his daughter and Mr. Smith all struggle with the same addiction.

Through these characters, addiction is explored from multiple angles to prove the Moral Premise of the story, which appears to be:

Addiction leads to death, but sobriety leads to life.

Mythic Story Structure.

So far, we have studied a generic story structure. This is a solid story structure and will serve you well.

However, we can take it up a notch by adding the elements of mythic story structure.

If this confuses you, simply work with the generic story structure we have been studying, but if mythic story structure intrigues you, read the books I suggest to fully master it.

Once you understand mythic story structure, you’ll have an immensely powerful tool in your creative toolbox.

Mythic Story Structure.

There are specific story patterns that speak deeply to our subconscious.

These patterns could be referred to as archetype story patterns as our mind appears to instinctively recognize them.

The fact we know these patterns gives them enormous power to entertain us and influence our life.

As a novelist, once you master these patterns, you will have a means to speak directly to the subconscious of your reader. Please use this power for good.

Here I’ll discuss two story archetypes. The Hero’s Journey and The Virgin’s Promise. The two are closely related and can be seen as mirror images.

The Hero’s Journey.

Joseph Campbell wrote that there is really only one myth, a mono-myth, although it is expressed in infinite variations. Campbell’s mono-myth is The Hero’s Journey.

It may not always be obvious, but The Hero’s Journey is essentially a warrior’s tale. It is masculine and outwardly focused even when a woman is the main character.

Although The Hero’s Journey dates back to before recorded history, its intentional modern use in story theory emerged with the first Star Wars movie.

If you intend to write action adventure stories, you will want to master The Hero’s Journey story structure.

To learn more about this pattern, I suggest you read the following books: The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell and The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler.

Not every story that follows the Hero’s Journey structure is an obvious warrior’s tale, but they do usually require courage from the main character.

A gentle romance could use the Hero’s Journey just as well, as I did in my novel Some Glad Morning.

Incidentally, Vogler’s book is a must read for anyone who is serious about a career as a novelist. In it, he shows how the writer’s journey is, in fact, a hero’s journey.

You see, The Hero’s Journey is a metaphor for the journey of life.

It shows us how to live wisely and how to overcome trials in order to reach our full potential. The Hero’s Journey is the journey to becoming fully human.

Below are the beats of The Hero’s Journey story structure. You’ll notice they are very similar to our generic story structure.

The Hero’s Journey Story Beats.

(Excerpted from The Virgin Promise by Kim Hudson, p.147)

Act I

- The hero’s ordinary world is established.

- A “Call to Adventure” or catalyst disturbs the hero’s world.

- Hero refuses the call to adventure.

- Hero crosses a threshold into a new world.

- Hero meets his guide or mentor.

- Hero crosses the first threshold.

Act II

- Hero endures test, meets allies and confronts enemies.

- Hero prepares for coming battles.

- Hero is defeated and succumbs to doubt & despair.

- A magical talisman is discovered to aid the hero in battle.

ACT III

- Hero begins the road back.

- A final battle is fought.

- The hero returns to his world with Elixir.

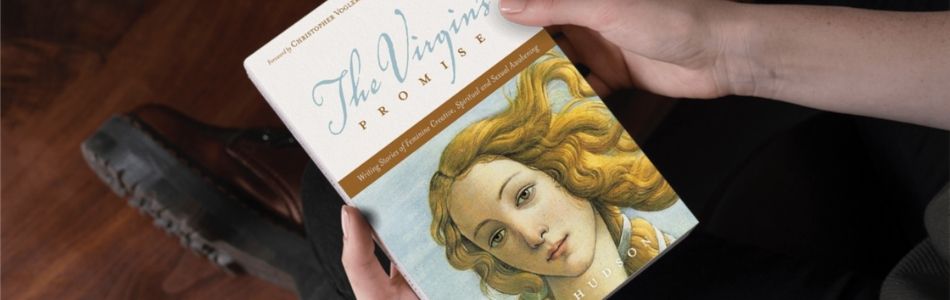

The Virgin’s Promise.

The Virgin’s Promise is a feminine variation of The Hero’s Journey. This doesn’t mean the main character has to be a woman, only that the story pattern is one of creation and self discovery.

The movie BILLY ELLIOT is a worthy example of the The Virgin’s

Promise story structure in action.

It’s the story of an 11-year-old boy who dreams of being a dancer.

To realize his dream, and to become fully himself, Billy must overcome the rigid masculine dominated mining town where every male is expected to work in the mines.

To learn more about The Virgin’s Promise read the book, The Virgin’s Promise by Kim Hudson.

Ms. Hudson coined the phrase and spent years uncovering this powerful story archetype.

Her book will tell you all you need to know to fully understand The Virgin’s Promise and how to accurately employ it in your writing.

For now, look over the story beats of The Virgin’s Promise and note how they relate to our generic story structure.

The Story Beats of the Virgin’s Promise.

(Excerpted from The Virgin Promise by Kim Hudson, p.147)

Act I

- Dependent World

- Price of Conformity

- Opportunity to Shine (Inciting incident)

- Dresses the part

Act II

- The secret world

- No longer fits her world

- Caught shining

- Gives up what kept her stuck

- Kingdom in chaos

Act III

- Wanders in the Wilderness (Moment of Doubt)

- Chooses her light

- Re-ordering/Rescue

- The kingdom is brighter

What’s Next?

The books I introduced to you in this lesson are optional.

It isn’t necessary that you read The Hero with a Thousand Faces, The Writer’s Journey or The Virgin’s Promise to prepare for the next lesson.

However, reading them will definitely expand your understanding of story theory and your options for structuring a novel.

I strongly recommend you add them to your library.

I also read these books as I plan a novel. Usually, early in my planning process I’ll know if the story fits The Hero’s Journey or The Virgin’s Promise.

Or, I will deliberately choose to write a story that follows one or the other at the start. Either way, I read the appropriate book to help me plan.

Christopher Vogler’s book, The Writer’s Journey, is worth reading for countless reasons. It will teach you many nuances of the Hero’s Journey, and it will help you understand your life as a writer.

In the next module, lesson, I’ll show you how to plan scenes.

Before then, be sure you understand how the Moral Premise works to focus a story. Watch the movies ANY DAY and MR. BROOKS to see how the Moral Premise shapes each scene.

Also go back to Dr. Stanley William’s book, The Moral Premise, and work through the second half of the book, beginning on page 108.

Use Dr. William’s step-by-step guidance to refine the Moral Premise of your novel.

It’s okay if you don’t entirely understand the Moral Premise of your story at this point.

Typically, the Moral Premise evolves as I’m writing my novel, but I start with a pretty good idea of what it is by following Dr. Williams’ guidance.